Gallstones

Gallstone disease is a common medical problem that affects 10 to 15 percent of the population of the United States, or well over 25 million people. About 1 million new cases of gallstone disease are diagnosed every year in this country. Half of these require treatment, with a cost to society of several billion dollars annually. In recent years, important advances have been made in the understanding of gallstone disease and in the development of new treatments.

What is the gallbladder, and what does it do?

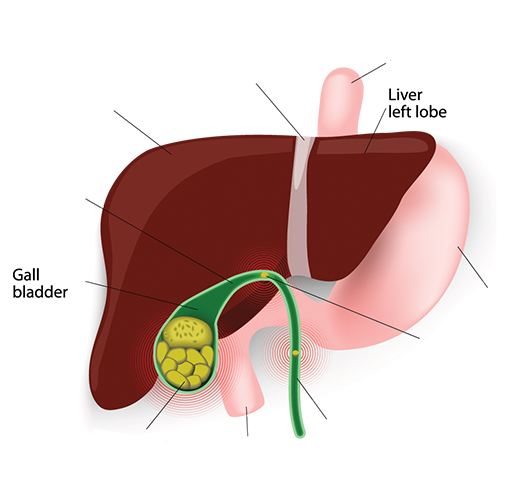

The gallbladder is a sac, about the size and shape of a pear, which lies on the undersurface of the liver in the upper right-hand portion of the abdominal cavity. It is connected to the liver and the intestine by a series of small tubes, or ducts. The primary job of the gallbladder is to store bile, which is produced and secreted continuously by the liver, until the bile is needed to aid in digestion. After a meal, the gallbladder contracts and sends the bile into the intestine. When digestion of the meal is over, the gallbladder relaxes and once again begins to store bile.

Bile is a brown liquid which contains bowel salts, cholesterol, bilirubin, and lecithin. About three cups are produced by the liver every day. Some substances in bile, including bile salts and lecithin, act like detergents to break up fat so that it can be easily digested. Others, like bilirubin, are waste products. Bilirubin is a dark brown substance which gives a brown color to both bile and stool.

What are gallstones and how do they form?

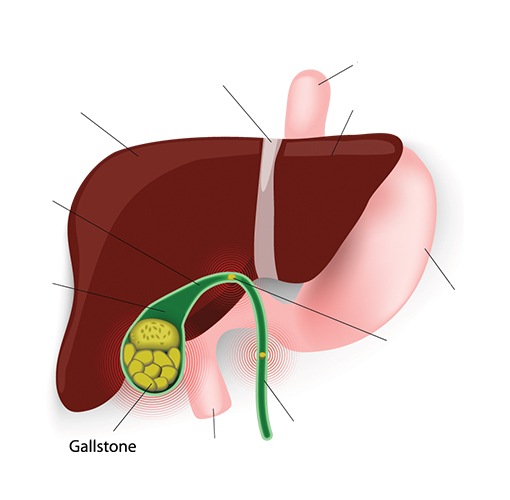

Gallstones are pieces of hard solid matter in the gallbladder. They form when components of bile (especially cholesterol and bilirubin) precipitate out of solution and form crystals, much as sugar may collect in the bottom of a syrup jar. In general, either cholesterol or bilirubin precipitates out of solution to form stones, but not both. In the United States, almost 80 percent of patients with gallstones have cholesterol stones. Gallstones may be as small as a grain of sand or as large as a golf ball, and the gallbladder may contain anywhere from one stone to hundreds. Sometimes the gallbladder contains only crystals and stones too small to see with the naked eye. This condition is called biliary sludge.

No one knows why some people develop gallstones and others don’t, but doctors do know some things which seem to increase the risk of developing stones. Anything which increases the amount of cholesterol in the bile increases the risk of cholesterol stones, and things which increase the bilirubin in bile increase the risk of pigment (bilirubin) stones. Other factors are probably also important in gallstone development, such as poor contraction of the gallbladder muscle with incomplete emptying of the gallbladder, and the presence of substances in bile which may speed up or delay precipitation of crystals. Many people with gallstones have a combination of factors. Exactly how diet affects gallstone formation is not clear, but diets which are high in cholesterol and fat, and low in fiber may increase the risk of developing gallstones.

Pigment (bilirubin) gallstones are found most often in:

- Patients with severe liver disease

- Patients with some blood disorders such as sickle cell anemia

Cholesterol gallstones are found most often in:

- Women over 20, especially pregnant women, and men over 60 years old

- Overweight men and women

- People on “crash diets” who lose a lot of weight quickly

- Patients who use certain medications including birth control pills and cholesterol lowering agents

- Native Americans and Mexican-Americans

What are the symptoms of gallstones?

The most typical symptom of gallstone disease is severe pain in the upper abdomen or right side. The pain may last for as little as 15 minutes or as long as several hours. The pain may also be felt between the shoulder blades or in the right shoulder. Sometimes patients also have vomiting or sweating. Attacks of gallstone pain may be separated by weeks, months, or even years.

It is thought that gallstone pain results from blockage of the gallbladder duct (cystic duct) by a stone. When the blockage is prolonged (greater than several hours), the gallbladder may become inflamed. This condition, called cholecystitis, may lead to fever, prolonged pain and eventually infection of the gallbladder. Hospitalization is usually necessary for observation, treatment with antibiotics and pain medications and frequently for surgery.

More serious complications may occur when a gallstone passes out of the gallbladder duct and into the main bile duct. If the stone lodges in the main bile duct, it can lead to a serious bile duct infection. If it passes down the bile duct, it can cause an inflammation of the pancreas, which has a common drainage channel with the bile duct. Either of these situations can be extremely dangerous. Stones in the bile duct usually cause pain, fever, and jaundice (yellow discoloration of the eyes and skin).

Many people with gallstones have no symptoms. Often the gallstones are found when a test is performed to evaluate some other problem. So-called “silent gallstones” are likely to remain silent, and no treatment is recommended.

What tests are used to diagnost Gallstones?

The most important parts of any diagnostic process are the patient’s description of symptoms and the doctor’s physical examination. When gallstones are suspended, routine liver blood tests are helpful since bile flow may be blocked and bile may back up into the liver.

Two excellent radiographic (X-ray) tests are used to determine the presence of gallstones. The first is abdominal ultrasound, in which a microphone is used to bounce sound waves against hard objects like stones. The second is an oral cholecystogram (OCG), in which an X-ray of a dye-filled gallbladder is taken after the patient swallows dye-containing pills. Both tests are about 95 percent effective in diagnosing gallstones. Ultrasound is more commonly performed because it is completely non-invasive (no injections), does not involve exposure to X-rays, and there are no pills to swallow. However, OCG may be recommended for some patients, especially if the ultrasound results are questionable.

Unfortunately, it is more difficult to diagnose gallstones once they have entered the common bile duct. Ultrasound is much less sensitive in the bile duct, and OCG cannot be used at all. The best tests involve putting X-ray dye directly into the bile ducts. A flexible swallowed tube can be used (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or ERCP), or a needle can be passed through the liver and into the bile ducts (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or PTC). These tests both carry small risks, require X-ray exposure, and may be uncomfortable or require the use of sedation. Their use is therefore reserved for certain patients.

What treatments are available for Gallstones?

Many new approaches to gallstone treatment have been tried over the past several years, but surgical removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) remains the most widely used therapy. This is partly because the newer non-surgical treatments are useful in only some gallstone patients, but surgery can be used in virtually all patients. Patients generally do well after surgery and have no difficulty with digesting food, even though the gallbladder’s function is to aid digestion. Surgical options include the standard procedure, called open cholecystectomy, and a newer, less invasive procedure called laproscopic cholecystectomy (“belly button surgery”).

In open cholecystectomy, the surgeon removes the gallbladder through a 5- to 8-inch incision. This procedure has been performed for over 100 years and is quite safe, although 4 to 5 days of hospitalization and several weeks of recuperation at home usually are needed.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a recent technique which was introduced in the United States in 1988. The surgeon makes several 1-inch incisions in the abdomen through which a tiny video camera and surgical instruments are passed. The video picture is viewed in the operating room on a TV screen, and the gallbladder can be removed by manipulating the surgical instruments. Because the abdominal muscles are not cut there is less postoperative pain, quicker healing, and better cosmetic results. The patient usually can go home from the hospital within a day and resume normal activities within a few days. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become common and is now used for 80 percent of all cholecystectomies in the United States.

Each approach has its advantages, and a doctor can recommend the best method for each patient depending upon the clinical situation. For instance, it may be difficult or dangerous to remove a severely inflamed gallbladder laparoscopically. It may also be more difficult to remove a stone from the bile duct laparoscopically, if one is found at surgery to have passed out of the gallbladder and into the bile duct. However, stones in the bile duct can frequently be left in place and removed at a later date using a non-operative method such as ERCP.

Gallbladder surgery may be complicated by injury to the bile duct, leading either to the leakage of the bile or scarring and blockage of the duct. Mild cases can frequently be treated without surgery, but severe injury generally requires bile duct surgery. Bile duct injury is the most common complication of laparoscopic than the standard approach.

What are alternatives to Cholecystectomy?

There are alternatives to surgery for both stones in the gallbladder and stones in the bile duct. ERCP can be used to find stones in the bile duct, as described above. When duct stones are seen, the doctor can widen the bile duct opening and pull stones into the intestine. This is commonly done when the gallbladder is being removed laparoscopically or when a stone is found in the duct long after gallbladder surgery. It may also be done to relieve symptoms from a bile duct stone, even when other stones are present in the gallbladder, if a patient is too frail to undergo gallbladder surgery.

Gallbladder stones can be dissolved by a chemical (ursodiol or chenodiol), which is available in pill form. This medicine thins the bile and allows stones to dissolve. Unfortunately, only small stones composed of cholesterol dissolve quickly and completely, and its use is therefore limited to patients with the right size and type of stones.

Two experimental approaches to gallbladder stones have been studied, but the results have thus far been disappointing. Patients with one or two larger cholesterol stones have been successfully treated with lithotripsy, a technique in which sound waves are focused onto stones which causes them to disintegrate. However, the fragments remain in the gallbladder unless urosdiol or chenodiol is taken to dissolve them. Patients with cholesterol stones have also been treated with methyl tertbutyl ether, a chemical which can be injected into the gallbladder until the stones dissolve. The chemical is harsh, and some complications have been reported.

A problem with all non-surgical approaches is that gallstones return several years later in about half the patients successfully treated.